In Predynastic times, Egypt was divided geographically and politically into Upper Egpyt and Lower Egypt. The Palette Of King Narmer is an elaborate document marking the transition from the prehistorical to the historical period in ancient Egypt, but was also an early blueprint of the formula for figure representation that characterized Egyptian art for three thousand years. As seen before, The king is portrayed as the largest figure showing his status and superior rank. The king's superhuman strength is symbolized in the lowest band by a great bull knocking down a rebellious city. Historical narrative is not the artist's goal in this work, but more important is the characterization of the king as a deified figure. The artist's portrayal of the king combined profile views of his head, legs, and arms with front views of his eye and torso. This composite view of the human figure also characterized Mesopotamian art and even some Stone Age paintings. Although the human figure's proportions changed, the method of its representation became a standard for all later Egyptian art.

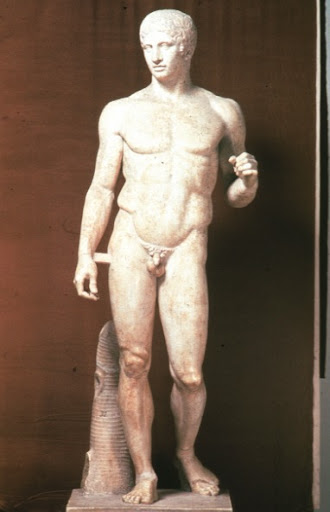

Egyptians created statues to serve for eternity. The idea was that sculptors created images of the deceased to serve as a place for the ka, should the mummies be destroyed. For this reason, and interest in portrait sculpture developed using stone so that the images would last forever. The limbs are not carved out of the stone, but remain in one big chunk so that the statue can be preserved. The portrait statues of Menkaure and Khamerernebty show conventional postures to suggest the timeless nature of these eternal substitute homes for the ka. Menkaure's pose is rigidly frontal with the arms hanging straight down and close to his well-built body. His hands are clenched into fists and his left leg is slightly advanced but there is no shift that occurs in the angle of the hips (controposto). Khamerernebty stands in a similar position with her right are circling her husbands waist and her left hang gently resting on his left arm. This pose represents their marital status, but they show no sign of affection and look straight forward out into space. This work is a good example of the Egyptian cannon of proportion.

The long life of Egyptian artistic formulas also can be seen in New Kingdom painting. New Kingdom painters did not always adhere to the old standards for figure representation In the fresco fragment from Nebamun's tomb the overlapping of the dancers' figures, their facing in opposite directions were carefully and accurately observed. The profile view of the dancers is consistent with their lesser importance. The composite view is still reserved for Nebamun and his family. Of the four seated women, the two at the left are conventional, but the other tow face the observer in an attempted frontal pose. Movement is suggested by the loose arrangement of the women's hair and this informality constituted a realization of the Old Kingdom;s stiff representational rules.

Even more revolutionary still was the art from the rule of Akhenaton. This ruler abandoned the worship of most of the Egyptian gods in favor of Aton, the universal and only god, identified with the sun disk. To him alone could the god make revelation, and Akhenaton's god was represented neither in animal nor in human form, but simply as the sun disk emitting life giving rays. This statue of Akhenaton retains the standard frontal pose of pharaohs, but the effeminate body, curving contours, long full lipped face, heavy lidded eyes, and dreamy expression were like nothing seen before. His sexless, curiously misshapen body with it's weak arms, narrow waist, protruding belly, wide hips, and fatty thighs either portrayed a physical deformity or a deliberate artistic reaction against the established style, paralleling the suppression of traditional religion.

The late period, as illustrated by the Last Judgment of Hu-Nefer shows a triumph of tradition. The figures have all the formality of stance, shape, and attitude of Old Kingdom art. Once again figures are portrayed stiffly in profile or twisted profile. The figures do not have depth and are one color with no shading. This depiction tells a story and once again, Hu-Nefer is shown to be in favor with the Gods. The Late Period pharaohs deliberately referred back to the art of Egypt's classical phase to give their royal image authority.